How things have changed! This is a brief account of the life of Revd Dr James Kidd (pictured) who was born on 6 Nov. 1761.

He was the youngest son of poor parents from Loughbrickland in County Down. His father died soon after his birth, following which the family moved to County Antrim where a friendly farmer paid for his school education. Later Kidd had sufficient means from running his own school, to go to Belfast to study English. He married Jane Boyd and in April 1784 they emigrated to Pennsylvania where he taught and also studied at Pennsylvania College. It was during this time that he chanced to see a written Hebrew character which started a new chapter in his life. He bought a Hebrew Bible, and with the help of a Jewish friend and by attending a synagogue he acquired fluency in Hebrew. At this time it was called Oriental Language and became his favourite subject. In 1792 he returned to Edinburgh University reading chemistry, anatomy, and theology, whilst earning money by teaching extra-collegiate classes in Oriental Language. In the autumn of 1793 he was appointed Professor of Oriental Language in Marischal College, Aberdeen, where he completed his theological qualifications and was licensed as a preacher by the presbytery of Aberdeen on 3 Feb. 1796. He was appointed evening lecturer in Trinity Chapel in the Shiprow. Then on 18 June 1801 he left Marischal College to become minister of Gilcomston Chapel of Ease where he stayed until his death on Christmas Eve 1834. During these years he took up the Abolitionist cause, founded the first Sunday School in Aberdeen and advocated the temperance movement. In October 1818 the College of New Jersey conferred on him the honorary degree of D.D.

His preaching was powerful and popular, reputedly to congregations of up to 2,000. But he was also a very forceful character who was not averse to being controversial. A source suggests he was an ‘Ian Paisley-like’ personality. One story told of him is that during one particular service a man wearing a distinctive red waistcoat fell asleep. The command came from the pulpit “Waken that man”. He was roused – for a while, but on falling asleep again there was a second reprimand from the pulpit. The third time, Dr Kidd picked up a small Bible which was to hand and threw it, accurately, at the sleeper – adding the words “Now, sir, if you will not hear the word of God, you shall feel it!” Dr James Stark published a biography of him in 1898. Dr Kidd had published a number of religious books.

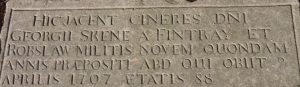

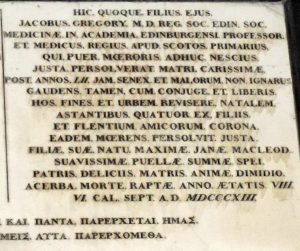

He is buried in the Kirkyard at the Kirk of St Nicholas Uniting. It would be easy to walk past his grave (shown in the photograph). It almost overhangs the central path from Union Street on the right hand side. The inscription for Dr Kidd is on the vertical face at the side of the path. In the recent SPECTRA 2017, there were illuminated ‘spiders’ around there. One can only imagine what he might have said!!