In October 2014, when we posted about the east end of the 12th century building, we indicated the intention for a series of posts giving further information about the stages of development of the present building. This is the first of this series with the rest appearing intermittently during the course of 2015.

When the archaeological dig began in 2006 it was not known what, if anything, would remain of previous buildings on the site, since each could have been demolished before erecting the next building. The reality was that a great deal was preserved. Thus, the lower levels of the whole of the chancel of the 12th century building were uncovered. Whilst both the north and south walls (the side walls of the chancel) were intact, the photographs in this blog are of the north wall. The stonework from the north wall was well preserved and can be seen in the first photograph. The wall is about 4 feet thick from inside to outside. However, some of the wall had been removed when the church building was being expanded in the late 1400s. This later building was to have massive pillars to carry much of the weight of the roof. These pillars required to have very stable foundations to avoid any danger of movement, so the builders made use of the existing walls. They did this by removing some stones to create circular ‘gaps’ into which large stones were placed to form the pillar bases. This ensured that there would be no east-west movement. The first photograph shows the north wall, viewed from inside the chancel, with a 15th century pillar base built into the 12th century wall. The pillar base is distinguishable by its curved shape (in the centre under the measuring pole). To its right is some ‘flat’ wall from the 12th century and then another pillar base at the right hand end of the wall.

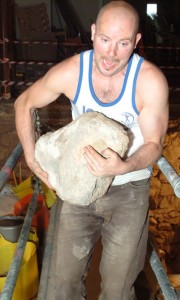

As part of the excavation it was necessary to remove both the original walls and the pillar bases. The size of some of the stones used to form the pillar bases was impressive. The second photograph shows Stewart Buchanan, deputy leader of the dig, carrying a smaller stone. The third photograph shows Stewart with one of the larger stones and deciding it is a bit too big for him to carry! Indeed to remove these it was necessary to erect a block and tackle to lift them into a mechanical tipper to get them out of the building, as shown in the final photograph. That the builders of more than 500 years ago could handle these stones and accurately place them into position deserves every credit.

To the east end the walls had been rebuilt to bond with the new east end as described in the 20 October blog. At the west end, the wall emerges from the walls of Drum’s Aisle which was the transept of that 12th century building. Drum’s Aisle is still used today and is part of the Kirk of St Nicholas Uniting and also houses St John’s Chapel, often known as the ‘Oil Chapel’. It is obvious, but it is worth noting that, until the late 1400s, the church building was far smaller than the present day building. Outside the walls (the opposite side to the photograph) was the graveyard which was taken inside the building when it was expanded in the late 15th century. Once the Mither Kirk Project redevelopment is complete it will be possible to see the western ends of both the north and south walls as they have been kept and will become a feature at either side of the early apse (see blog on 4 May 2014).

The photographs, which are copyright Aberdeen Art Gallery & Museums Collections, are used with permission.