Most churches of any size have a pipe organ, although, regrettably, their use is decreasing. There is some evidence that they were first used more than 1000 years ago. However, it was only in the 1500s when technological developments, initially in Germany, enabled the organ to be far more versatile so that it became a regular feature in churches. Organs are very versatile and can produce a range of different sound qualities, such as might be suitable to accompany a congregation or choir, during quiet meditation, before the service or as an exhilarating postlude as people leave. Indeed the organ has been described as a ‘one-person orchestra’.

Little is known of the music at St Nicholas Kirk, Aberdeen during the Middle Ages. However, the Burgh Accounts for 1437 indicate the payment of 26 shillings and eight pence “for blowing the organs” – well before mechanical blowers. There are also indications in the records that high standards of music and behaviour were expected from the chaplains and choir boys. For example, in 1533 the entire choir, apart from one aged chaplain, was dismissed! In 1544 John Fethy was appointed to “have charge of organ and sang schule”. The Reformation brought changes to church music and in 1574 the civil authorities ordered that the organ should be dismantled and sold for the benefit of the poor. It seems that the latter part of the instruction was not obeyed because, two hundred years later, the pipework was found stored in St Mary’s Chapel.

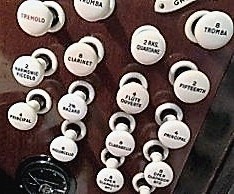

This blog is the first of a series on the organs in the Kirk of St Nicholas. The first photograph shows the console of the former East Kirk organ. It looks complicated! However, it may become easier to understand with an explanation of how it works.

In the centre are three manuals. Each manual is similar to a piano keyboard, although shorter. Each key is related to a note of a particular pitch, as with the piano. It is common for organs to have more than one manual – the normal is two or three, but large organs can have up to five. A note sounds for as long as the key is held down, unlike a piano where the sound fades fairly quickly. On each side of the manuals are the ‘stops’. These connect the keys on the manual to pipes in the organ to produce the sound. Different lengths of pipe produce different pitches. For each stop there is a rank of pipes each of different length to produce the whole range of notes. The material and structure of the pipe produces different sound quality and tone – such as sounding like a flute, an oboe, a trumpet, strings as well as the basic ‘organ sound’ called a diapason. These are named on each stop, but there is also a length marked on them. The ‘basic’ length is 8 foot (8’). If this is used it gives the same pitch as a piano. However, there are stops which indicate different lengths, such as 4’ (an octave higher), 2’ (two octaves higher) 16’ (an octave lower) and 32’ (two octaves lower). The organist can use combinations of stops which enable one key to play several notes at different pitch and by combining several different tonal qualities, a very wide range of sounds can be produced.

There is also a pedal board (not shown on the main photograph but shown in the second photograph). This is, in effect, the lower half of a manual but made of larger pieces of wood to be played using the feet. Most organs now have a concave shape to the pedal board to make it easier for the feet to move around. The organist uses both feet as necessary and can play using either their heel or toe.

It will be noted that there are other ‘bits’ on the organ console. Under each manual there is a series of white buttons. These are called ‘thumb pistons’ because they are most easily operated with the thumb whilst playing. These are replicated by the studs above the pedal board (called toe pistons). Their function is to activate pre-set combinations of stops, thus allowing the organist to quickly change the settings. Other buttons allow connections to be made between each of the manuals and pedals, so that notes played on one are also sound on the coupled manual.

Finally, below the manuals, in this organ there are three larger tilting pedals. The two on the left are ‘swell pedals’ used to open or close louvre shutters which enclose some of the organ pipes. This is a way for the volume of sound to be increased or decreased by the organist whilst playing. The right hand of the three (shining in the photograph) is a general crescendo pedal; using it adds or subtracts stops to increase or decrease the overall volume. In the centre, above the top manual, there are indicators to show the positions of the swell and crescendo pedals.

The last photograph shows what most people think of as ‘the organ’ where the pipes are. The pipes which are seen in this case are dummies. All the actual pipes are behind the dummies, enclosed in the louvered shutters.