For Valentine’s Day, we feature possibly one of the more romantic finds during the archaeological dig.

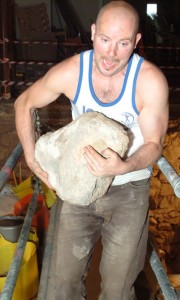

Quite a number of items of jewellery were found during the archaeological excavation. In the early part of June 2006 one particular burial of a young man was being uncovered. Resting on his ribs, just above where the heart would have been, was a silvered heart shaped brooch with what could be an arrow through it. The photograph shows the brooch in situ just as it was uncovered.

Cupid was a god in Roman mythology (known as Eros in Greek mythology) who was often portrayed as a winged youth or cherub. From quite an early date the iconography included a bow and arrow, so that anyone pierced by one of Cupid’s arrows would be filled with love and desire. In the mythological stories Cupid’s arrow was often used as a device for progressing the story. The idea of Cupid or Eros has developed and changed over the centuries, but remains a firmly associated with the heart and human love.

St Valentine, is another of the early Christian saints about which nothing is certain. Despite this St Valentine’s Day is a feast day in the Anglican and Lutheran churches amongst others. There was no link between St Valentine and romance until Chaucer mentioned it in the late 14th century. The idea developed and by the 17th century exchanging romantic messages at the feast of St Valentine was well established. By the end of the 18th century collections of suggested verses were published! The introduction of improved postal services encouraged the development of Valentine Cards in the 19th century and it is now big business. Images of hearts and arrows certainly appear regularly in designs.

Of course there is no way of knowing the detailed history of this particular brooch, but it is nice to imagine a grieving young woman leaving this token of eternal love on the body of the deceased at the time of burial.