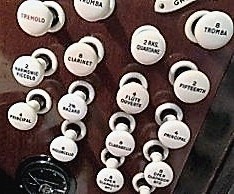

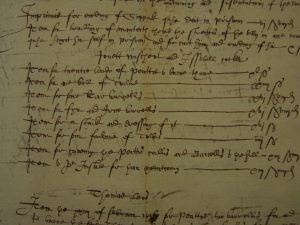

In the earlier blog on 20th July, the former East Kirk organ was used to illustrate the basic working of a church organ. More than a century ago, the first organ of recent time in the East Kirk was a two-manual instrument built in 1887 by Wadsworth Bros of Manchester. This was enlarged to three manuals by the local firm of EH Lawton in 1902. Ernest Henry Lawton was born in Sheffield and after serving his apprenticeship worked for Wadsworth’s for 9 years before setting up on his own business in Merkland Road East in Aberdeen in 1898. The three-manual organ of 1902 was never deemed satisfactory and by the 1930s was regarded as worn out. During the reordering of the East Kirk interior in 1936 a new organ was purchased from the Compton Company. This has three manuals and 69 stops being built on the ‘extension principle’. This method of construction uses an extended range of pipes of a particular sound type (called a rank) to produce the sound for 16, 8, 4 and 2 foot stops. This design was particularly useful where there was insufficient space to house the large number of pipes needed in a conventional design.

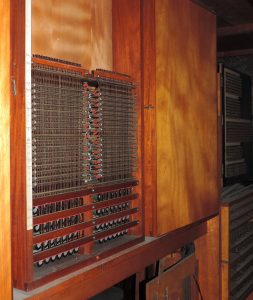

Apart from the console, the working parts of a Compton organ are in two sections. One is the actual pipes which produce the sound. In the East Kirk these are located at the back of the gallery. The other is the electrics which operate the extension principle, which for the East Kirk organ are located in the tower. Also in the tower is the blower which produces the air for operating the pipes. A few photographs are included with this blog to show some of the hidden ‘works’ of the organ. It can be seen that the shape and material used to make the pipes differ. These produce different sound qualities. Within a ‘rank’ of similar pipes, the different lengths produce the different pitches – the shorter the pipe the higher the pitch. Other photographs shows some of the panels of electrics in the tower. They are almost a work of art in themselves! The blower is a large fan driven by an electric motor – in days gone by the air would have been produced by a person pumping the bellows.

The redevelopment of the interior of the former East Kirk as part of the Mither Kirk Project gave the OpenSpace Trust a series of dilemmas. Indeed, to allow the archaeological dig in 2006 the console had to be removed and all the connections between it and the tower removed. So at present it can no longer be played unless major work was carried out. Reluctantly, the OpenSpace Trust made the organ available to anyone who could offer it a new home and restore it to playing order once again. We are really pleased to say that, towards the end of September, it will be dismantled and taken to Dorset where a new life awaits. It served services in the East Kirk for 70 years and in the future it will be able to lead music once more in a new setting.