There are several large memorials along the wall of the Kirk of St Nicholas Kirkyard which backs onto Back Wynd. One of these is for George Davidson of Pettens. Pettens was a farm just north of Balmedie, but George Davidson acquired a large estate covering the area near modern day Kingswells, Newhills and Bucksburn.

It is not known when he was born, nor who his parents were. He never married and was probably illiterate. Despite this he was a burgess of the city of Aberdeen and amassed a substantial amount of wealth, part of which he used to extend the estate. However, most of his wealth was used to fund projects for the benefit of others. Travelling home from Aberdeen one day he saw a man nearly drown in attempting to cross the Buxburne (the modern day Bucksburn, which flows through the Aberdeen suburb of Bucksburn to join the River Don). This moved him to have a stone bridge built, including the provision of money for its upkeep. In addition, he repaired the bridge at Inche (Insch), built the chapel at Newhills and the walls around St Clement’s Church in Aberdeen, where there is a memorial plaque to mark his generosity. Apart from this type of beneficence he also left endowments to the ministers of both St Nicholas and St Clement’s Churches.

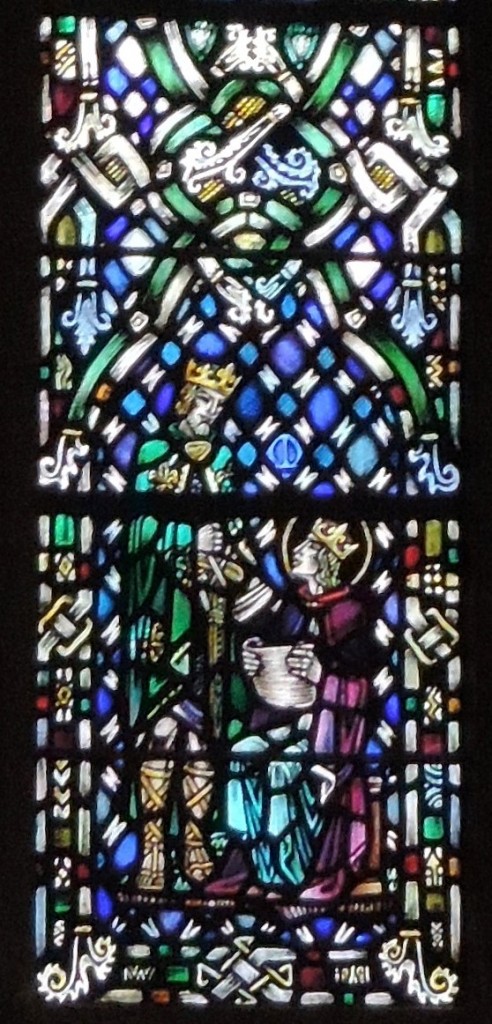

As can be seen in the photograph, the central part of the memorial is a Latin inscription. The following is a translation, taken from ‘Collection of Epitaphs and Monumental Inscriptions: Chiefly in Scotland’ published in 1834, which indicates the wide range of good works which George Davidson did before his death in 1663.

“To the eternal memory of George Davidson of Pettens, a man truly notable for the integrity of his life, and profuse liberality towards the poor, and for his piety towards God, and who deserved very well from the church and all the commonwealth, and from this city of Aberdeen. This man, beside many donations for the perpetual help of the poor and publick uses, caused the bridge of Inche to be repaired, and the bridge of Buxburne to be built of a notable structure. He gifted to the church of Aberdeen the lands of Pettens and Bogfairlie, with certain sums of money, for the perpetual use of a preacher of God’s word there; he also caused build the church of Newhills, and, for the more increase of the kingdom of God, by a singular example and preparative, he dedicated and mortified the saids lands of Newhills also, for the maintenance of the ministers of the gospel thereat. He died in the year 1663.”