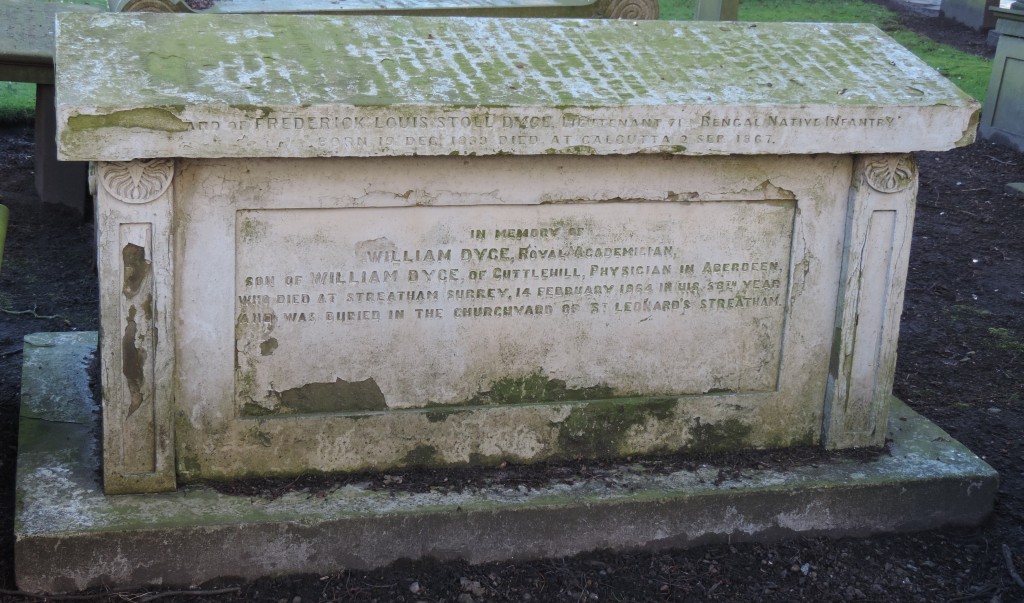

Finding gold in most archaeological digs is unusual. Not surprisingly very little was found during the dig in 2006 inside the former East Kirk of St Nicholas. Perhaps Aberdonians were very careful with their valuable items! However three gold items were uncovered during the excavation.

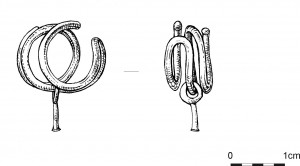

The first photograph shows a spiralled gold object found at the beginning of May 2006 in a family burial vault. It has not been accurately dated, but coins in the same vault suggest that it dates from 1690 at the latest, but could be earlier. Exactly what it is remains a little obscure, but it is thought that it is probably an earring. The second illustration is a drawing of this item, included as much as anything to show the skill of the archaeological illustrator. Preparing detailed drawings such as this is an important step in the post-excavation work which follows a dig. It is a great skill to be able to produce such exquisitely detailed records of the items found in the dig, often showing detail which does not show in a photograph.

In early September 2006 a gold ring was found – shown in the second photograph. It is a simple ring with a cuff on it, again perhaps an earring or possibly a finger ring. The archaeologist who found it had been involved in digs for 25 years and this was the first gold item he had ever uncovered. That shows how unusual gold items are!

The third photograph shows another gold ring, similar to the second one. However, this was not found until after the dig was complete when the human remains were being cleaned. It was found in a skull as this was being cleaned.

(The illustrations are copyright Aberdeen Art Gallery & Museums Collections and are used with permission).